The one certain thing in a creative freelance life is that we have to be able and willing to deal with uncertainty. Whether it’s where our next job is coming from or what new skills we need to acquire when we get there, we have to be adaptable and quick to learn. And most of us are already, but sometimes it can feel difficult.

The good news is that our brains are geared up for life-long learning. Scientists are finding increasingly sophisticated ways to look at the brain to see how it changes in response to our experiences, which is what learning is.

A recent series on BBC4 called ‘The Brain with David Eagleman’ had some fantastic examples of this research. Unfortunately this series is no longer available on iPlayer, but there are clips available and if it is on again, I highly recommend you watch it.

In the series they took MRI scans of taxi driver’s brains while they were studying ‘The Knowledge’, in which they have to learn a vast number of routes and street names in and around London. They discovered that the area of the brain that deals with this type of memory significantly increased in size over the time they were studying. The brain’s capacity for storing this kind of information literally grew!

Another example of this flexibility is shared in a TED talk with neuroscientist Dr Sara Lazar called How meditation can reshape our brains. When Lazar took up yoga in response to a training injury occurring while preparing for the Boston Marathon, she started to notice changes in her mood and attitudes and, being a brain scientist, she decided to study this. Like the taxi driver experience, she was able to measure changes in the brain directly resulting from people regularly practising meditation, e.g., the stress areas got less active and smaller, and the social and empathic areas got more active and larger.

Of course not all examples are positive. I’m reading a book on addiction at the moment, and the same phenomenon is at work here too. As the addiction takes hold, the parts of the brain dealing with pleasure seeking and focus expand and coordinate, driving the addictive behaviour. More good news though is that the brain is constantly open to change, so new behaviours can be learned and unlearned even with addiction.

As far as the brain is concerned the secret to learning is repetition. When we do something for the first time, we lay down a number of new connections in the brain. As we repeat this activity, additional layers are laid on top of the original pathway, allowing the pathway to get bigger and bigger until it becomes a ‘main road’ in our thought processes. So, a new habit goes from being awkward to becoming more comfortable until over time it becomes automatic.

So that’s a brief summary of the technical end. It turns out that learning is not only possible but unavoidable throughout our entire lives. So why does it still feel tough sometimes?

As mentioned above, learning something new takes repetition. This is the same with changing old patterns and habits. So it can be useful, while the brain is getting on with its stuff, to have another way of considering how you are feeling throughout the learning process. That way, if you hit a tough bit, it can help you understand that you are in a necessary part of the process of learning and that, with perseverance, you can push past it and back into the fun bit again.

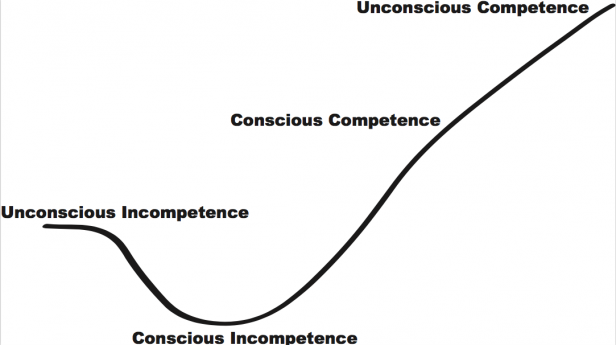

The ‘Conscious Competence’ model (see diagram below) is a helpful tool to use when learning a new skill.

Lets consider how this model applies to learning to play a musical instrument such as the violin:

Unconscious incompetence

Before we ever pick up the instrument, we are unaware that we are missing any skills or abilities. We can’t play, but we’ve never tried, so it’s not a problem. We don’t know what we don’t know.

Conscious incompetence

Once we have decided to learn, we pick up the violin and bow, try to get a note out of it and realise that it’s not as easy as it looks. There are lots of things to coordinate, the angle of the violin on your shoulder, how to hold your arm, where to put your fingers, how to get a tuneful note.

This is when you realise that there is a gap between what you want to do and what you are able to do. This is the stage when many people give up. This feeling can be so uncomfortable that it might feel easier to throw the towel in. However, this is an essential stage of learning: if you don’t ever work out what it is you specifically need to learn and press on through, you will be stuck at the unconscious incompetence stage and not move forward.

Conscious competence

You persevere and start to gain some proficiency on your instrument. You learn what works, where to place your fingers, how to hold the instrument and bow and you begin to be able to make music (of sorts) even if you have to concentrate quite hard to remember to do it all. This is conscious competence, you know what you know, and can take pleasure in your growing abilities.

Unconscious competence

It takes years to learn to play the violin proficiently, but as your skills develop there will be moments when you pick up your instrument and just play without thinking about where your fingers are, or how you are holding it. You will just create music. This is unconscious competence. If someone asked you how you did it, you would struggle to explain it, as you are no longer thinking about the step-by-step mechanics of the experience. Many of the skills have become automatic.

On-going Cycle

The unconscious competence stage is not an end point. Say you have been trained classically, and get the opportunity to play Jazz. Here you have a whole new set of rules, some new moves and ways of using your instrument that feel uncomfortable to you as it goes against all your existing training.

Suddenly you are once again in the conscious incompetence stage of learning. Then, as you work out how to do it on your own/with help and or instruction, you move into conscious competence then finally into unconscious competence again.

The same happens when you go from an amateur orchestra to professional one, the standards are higher and you become conscious of gaps in your skills. Instead of getting disillusioned, recognise that you have dipped back to the conscious incompetence stage, and that this is an opportunity to improve once more.

When we attempt to learn any new skill, the above cycle repeats itself to a greater or lesser extent including what can sometimes be a difficult unconscious competence stage. By recognising that this is all part of the learning process, I hope you’ll be encouraged not to give up at this stage but to stick with it until you achieve your goals.

If you are interested in the book I mentioned on addiction, it’s called The Biology of Desire by Marc Lewis

To help you learn, we have a range of venue-based and online opportunities created especially for you. For example, topics covered by our e-courses include: Overcoming Freelance Challenges and Negotiation for Freelances. We also now have recordings of our live webinars available on our website which cover topics like Building confidence and Creative Productivity.